The process of selecting artists is a little different for me than it is for many editors. Most editors have a full roster of projects in need of artists, so when they find an artist that they like, often they have a project immediately available that they can offer them. But as a freelance editor — which is still a rarity in comics — I’m only working on a handful of projects at any given time. So when I discover a new artist that I like, I save their info, bookmark their website…and I wait. I wait for a project to come my way that would really suit that artist’s style.

Sometimes I may wait to work with a particular artist for years, but when I do finally find a good project for the artist, that’s really just the first step. Since I work primarily on licensed comics these days, I’m not the only person who needs to approve creative teams. The publisher and the licensor both get a say, and the only way they can really judge whether an artist is fit to draw Warcraft, The Dark Crystal, Fraggle Rock or The Muppets is to see some sample art.

Trust me, if there was a way of getting the guys in charge to sign off on an artist that didn’t require asking for sketches and sometimes full pages on spec, I’d be all in favor of it. But there really isn’t, particularly when it comes to the licensor. They want to know what their characters will look like rendered in the artist’s style.

This audition material is often truly remarkable, and outside of the occasional sketchbook section, it’s usually not seen by readers.

Muppet Robin Hood completed its four-issue run two years ago, and with a new Muppets trailer playing in theaters, it seemed like a good time to revisit it and share some fun behind the scenes stuff. Obviously, the Muppets are still © The Muppets Studio and none of this stuff should be considered official Muppet canon. (Especially since I’m pretty sure that the official Muppet canon is property of Gonzo. At least, you’d think so considering he’s always the one who’s getting fired out of it.) Also, I should probably mention that I wasn’t the editor of Muppet Robin Hood. I was the writer. The editor was Paul Morrissey, but my points about sample art still hold true.

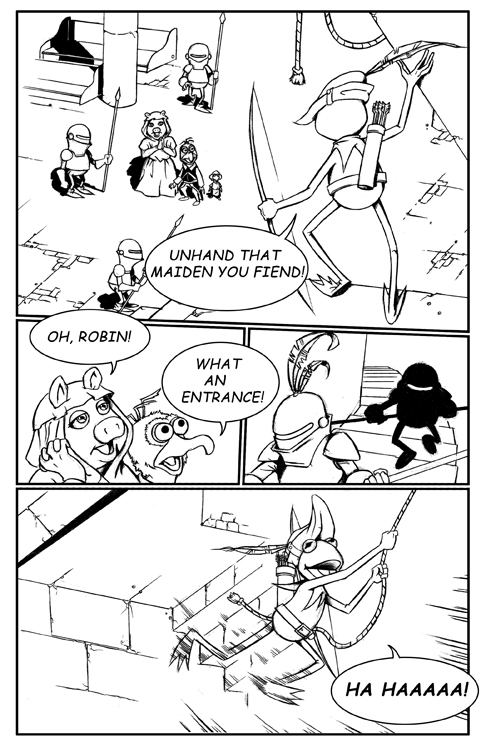

The artist on Muppet Robin Hood was Armand Villavert, Jr., an illustrator that Paul Morrissey and I knew from TOKYOPOP. Armand really wanted the gig. So much so that to get Disney to sign off on him, he didn’t just provide character sketches, he came up with a couple of sequences and wrote a complete script for them. These were never meant to be an actual part of the comic, but they’re as funny as anything I came up with. None of the below was written by me. This is all Armand.

The below two pages were colored by T. J. Geisen. I’m not sure why he wasn’t hired to color the entire comic as I think he did a great job on these samples. Note the extra detail and texture he’s provided, which helps give Armand’s line art a little additional depth. That wasn’t an approach used in the actual comic, but it probably should have been.

If you’ve read Muppet Robin Hood and you’re perceptive when it comes to art styles, you may notice something else about the above pages. They’re drawn in a different style than the one used in the comic. Armand originally drew the Muppets less stylized, opting to try to reproduce the actual look of the puppets a little more faithfully. However, after the success of Roger Langridge’s Muppet Show comic, a decision was made to render the Muppets in a style closer to his.

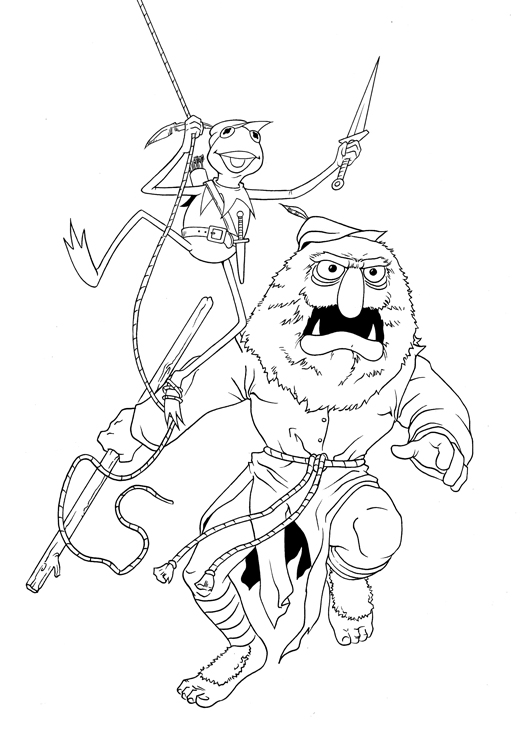

I understand the reasons, but I’m rather fond of this initial approach and can’t help to wonder how the book would’ve looked if we’d stuck with it. The above pages and the below sketches of Kermit and Sweetums at least give us a hint.

Later this week, we’ll look at how much differently a scene can read when drawn by different artists following the same script, and get a glimpse of what Muppet Robin Hood might have looked like had it been drawn by another popular Muppet artist. Stay tuned!